Primary Pulmonary NUT Carcinoma with NSD3-NUTM1 Fusion

Jaffar Khan, Rumeal Whaley, Liang Cheng

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA

*Correspondence: Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA. Email: lcheng@iupui.edu

Abstract:

NUT carcinoma is a rare carcinoma that is highly aggressive and resistant to multiple treatment modalities. It is estimated to represent 0.6% of the non-glandular lung carcinomas. Undifferentiated morphology presents a challenge in arriving at a correct diagnosis, especially on biopsy specimens. Since its original description, the demographics are shifting to include older individuals and non-midline structures due to the broader availability of ancillary studies. Classically, NUT carcinoma harbors a t(15;19)(q14;p13.1), resulting in BRD4-NUTM1 gene fusion, while other fusion partners are rare. We present a case of primary pulmonary NUT carcinoma with NSD3-NUTM1 (WHSC1L1-NUTM1) fusion in a 78-year-old man. The patient was a lifelong nonsmoker with no significant past medical history who presented with abdominal pain. Imaging revealed a 1.4 cm nodule in the right lower lobe. A subsequent biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated carcinoma. Next-generation sequencing was performed, and NSD3-NUTM1 (WHSC1L1-NUTM1) fusion. A diagnosis of primary pulmonary NUT carcinoma with NSD3-NUTM1 was made. The patient was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy followed by adjuvant radiation therapy and dual immunotherapy with a PD-L1 inhibitor. Unfortunately, the patient progressed on therapy with multiple liver, lung, and pleural metastases. He died 13 months after diagnosis

Keywords:nut

NUT carcinoma, pulmonary, aggressive tumor, BRD4- NUTM1, squamous.

Introduction

NUT carcinoma is defined by NUT carcinoma (NUTM1) gene rearrangement, most often t(15;19)(q14;p13.1) translocation, resulting in the BRD4-NUTM1 fusion gene while other fusion partners are rare.1-3 In a meta-analysis by Giridhar et al.3 (PMID 29356890) of the 119 cases only three cases were categorized as ‘NUT variants’ (non BRD4 and BRD3 fusions). In a series of six pulmonary NUT carcinomas Chen et al. reported two cases of NUT carcinoma with NSD3-NUTM1 fusions. The cell of origin is unknown and has been reported in various anatomical sites. The thorax, head and neck account for the majority of cases.3,4 The clinical course is often aggressive and short lived.3,4 NUT carcinoma often presents as rapidly growing mass with metastases at presentation in 39.8% of cases.3 NUT carcinoma was originally termed NUT-Midline carcinoma due to the exclusive (at the time) midline occurrence of these tumors.5,6 Demographics are shifting to include older individuals and non-midline structures due to the broader availability of ancillary studies.

Case Presentation

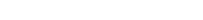

A 76-year-old male who had no significant past medical history presented with right lower quadrant abdominal pain. Computed tomography (CT) revealed no abdominal abnormalities; however, a 0.9 cm noncalcified nodule was found in the right lower lobe of the lung. Chest CT re-demonstrated the nodule with no associated adenopathy. The patient was a lifelong nonsmoker, and follow-up imagining was recommended. Two months later, a chest CT revealed that the nodule enlarged to 1.4 cm with calcified paratracheal nodes. Subsequent CT-guided biopsy revealed a proliferation of small round blue cells [Fig 1A]. The cells were uniform and without significant pleomorphism. The mitotic rate was brisk, with numerous apoptotic cells and necrosis. In an attempt to further classify the neoplasm, immunohistochemical staining was performed. The tumor cells were positive for p40 [Fig 1(inset)]. The following markers were negative: TTF1, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, and chromogranin A. The tumor was diagnosed as poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed a pulmonary nodule and the right mediastinal lymph nodes to be PET avid. Distant metastases were not identified.

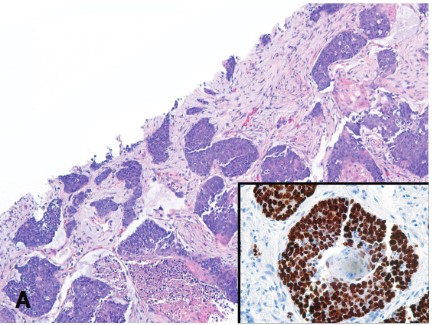

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the mass, designated at the time as a “pancreatic head mass,” revealed loose clusters of tumor cells with abundant granular cytoplasm. The nuclei were round to elongated, with marked variations in size, granular chromatin, and scattered pseudoinclusions. The cytoplasm appeared amphophilic in the H&E-stained cell block slides [FIG1A-C]. Based on cytomorphology, our differential diagnoses included ductal adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and peripheral nerve sheath tumors. While anonucleosis suggested ductal adenocarcinoma, the cytoplasm was granular instead of mucinous. Granular chromatin and cytoplasm suggest neuroendocrine differentiation; however, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are typically less cohesive with uniform, eccentric nuclei. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are usually composed of spindled cells but can be more pleomorphic. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the cell blocks. The tumor cells were positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and GATA3. Weak to moderate staining was observed for S100. The tumor cells were negative for pan-cytokeratin and SOX-10. The Ki-67 index was low (~ 1 %). Morphological and immunohistochemical features pointed towards a diagnosis of paraganglioma. Positive GATA3 and negative pancytokeratin expression have been argued against pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [14].

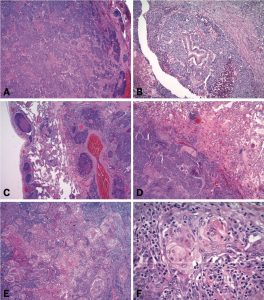

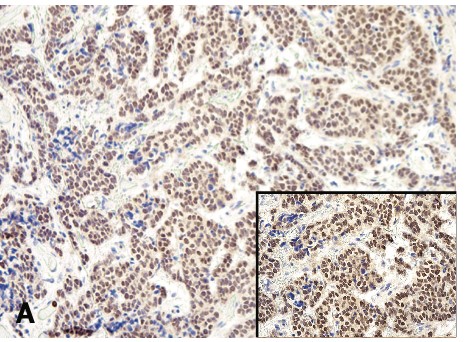

Preoperative laboratory testing revealed markedly elevated plasma normetanephrine and mildly elevated plasma metanephrine levels, suggestive of a paraganglioma. Surgical resection was performed, and gross examination showed a 7.5 x 5.4 x 4.2 cm well-circumscribed, tan-pink, solid mass with central hemorrhagic cystic changes [FIG2]. A small amount of fat was also attached. Microscopic examination revealed trabecular and solid architecture with sclerotic fibrovascular septa. Alveolar (Zellballen) architecture was not prominent. The tumor cells had abundant amphophilic cytoplasm and markedly pleomorphic nuclei with scattered pseudo-inclusions [FIG3]. There was no tumor cell necrosis, vascular invasion, or invasion of the adjacent structures. Only one mitosis/10 HPFs were observed. The surgical margins were close, but negative. Immunohistochemistry showed tumor cell positivity for synaptophysin, chromogranin, and GATA3. There was weak tumor cell staining for S100; however, no S100 or SOX-10 positive sustentacular cells were observed. Pan-cytokeratin staining was negative. The Ki-67 labelling index was A fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of paraganglioma was confirmed. Next-generation sequencing revealed an NF1 mutation consistent with a history of neurofibromatosis. No SDH mutation was detected.